Count Me In: Volunteers Are an Essential Part of Doing Business

By Meg Friedman

This is about the value of volunteers.

Volunteer labor has been a substitute for capital since the start of the regional theater movement – and certainly, freely given labor has been a reality of community life for much, much longer than that.

It is time for the theater industry to recognize that volunteer labor is part of the cost of doing business. Without this subsidy, in the ticket-takers and annual fund callers and interns and more, many theaters would be fundamentally different – and some would close. (Imagine a theater festival without volunteers – pretty bleak, right?) In no way am I advocating for a field where all personnel are paid staff. As Michael Stotts gently observed, in a 2017 conversation, it’s important for the community and the theater to have the special relationship that comes from giving time. Community endorsement must be represented in more than dollars and cents. But the status quo around volunteer labor cannot survive the next fifty years without meaningful change.

Volunteer time has value, and if all our value-assessing tools are in dollars and cents, then time given should be accounted for in financial reporting. This will, and should, prompt changes in how funders and theaters evaluate success.

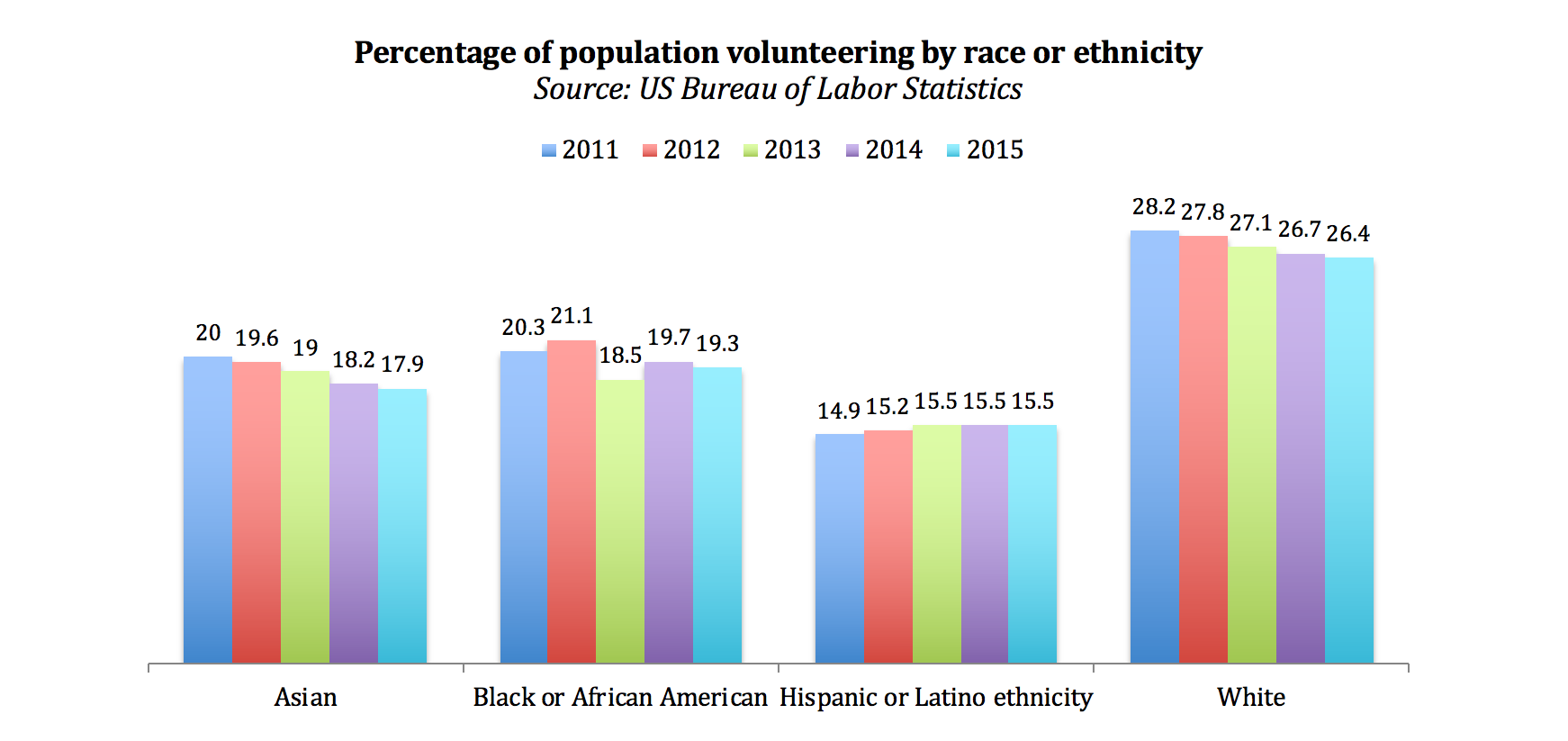

Volunteers are part of the workforce. They should be counted and understood as deeply as the paid members of that workforce. How can the theater sector advocate for better inclusion of women, people of color, youth, people with disabilities, and more and more marginalized groups, without counting volunteers? We manage to count so much already – the thirst for data is almost comical (a colleague recently described one organization with over 160 Key Performance Indicators – one of which is “How Many KPIs Do We Have”). If we state that the number of people involved in theater must be representative of any particular place or people, we have to include all the people who are making theater happen.

What next?

If we don’t develop new ways to value, welcome, and stay engaged with tomorrow’s volunteers, the not-for-profit theater sector’s most valuable subsidy will dry up. Plenty of theaters worried about going belly-up in the wake of the Great Recession (and plenty did – but many more have sprung up to take their place). Theaters are now, as I write this, in the third year of rallying along with museums, libraries, and other vital cultural institutions to save the National Endowment for the Arts, the Institute for Library Sciences, and other crucial sources of federal funding. But the decreasing number of volunteers is a ticking time bomb that has no federal budget line, and represents far more value than the NEA’s $152 million budgeted dollars in the last year.

So, what does that mean? Lots of things, for lots of stakeholders. Below are some broad suggestions geared toward funders, theater workers, and the people who work or volunteer in any supervisory role in theaters.

Count volunteers. Not just a headcount – understand the demographic and characteristics, and benchmark these data against peer theaters. TCG’s annual budget survey is tremendous and provides a model for this kind of peer benchmarking.

Find or make new pathways to connect volunteers to theaters. What tasks can volunteers do remotely? From board meetings to social media to script coverage to travel planning, plenty of tasks can be given to volunteers that do not require them to appear, dressed a certain way and already having eaten dinner, at 6:00pm sharp. Game-ifying these experiences could also minimize the sense that this is just work, done for no pay.

Don’t “throw some volunteers at it.” Talking about volunteers as a trivial or infinite resource undermines the value of the gift and the experience on all sides. Teaching young theater professionals – many of whom are stepping away from unpaid internships themselves – to value and respect volunteers is essential to building the sector. Yesterday’s interns are tomorrow’s executives, and those of us in between those points have a responsibility to be inclusive of the workers around us, regardless of their pay scale.

Theaters are viable because of volunteer hours. Counting who volunteers, and the value of their time – and understanding how volunteers identify – is an imperative to continuing relevance.

This blog has been adapted from Count Me In: Leveraging Generational Differences To Sustain Volunteer Engagement. For the full report, click HERE. Here are the links to Part 1 , Part 2, and Part 3.

_format-1500w.png)